Four years ago, Myles David Jewell, a 31-year-old filmmaker, began combing through his late grandfather’s old police files on the Boston Strangler case from the early 1960s. Working closely with his uncle John DiNatale, they uncovered details showing Detective Phil DiNatale’s dogged persistence, as well as his frustration that the investigation had never led to the prosecution or conviction of Albert DeSalvo.

In an 80-minute documentary called “Stranglehold: In the Shadow of the Boston Strangler,†they describe how Mr. DeSalvo became a suspect in the slayings of 11 women from 1962 to 1964, a killing spree that terrorized Boston and the surrounding areas.

Mr. DeSalvo eventually confessed to the murders while in jail on rape and other charges. And the killings stopped. But questions about his confession fueled speculation over the last 50 years about his guilt from people including family members of some of the victims.

On Thursday, Mr. Jewell said his grandfather could finally rest in peace. Boston law enforcement officials announced new DNA evidence linking Mr. DeSalvo to at least one of the murders. As my colleague, Jess Bidgood reported, seminal fluid gathered in January 1964 at the crime scene of a 19-year-old victim, Mary Sullivan, has been linked to Mr. DeSalvo.

“There was no forensic evidence to link Albert DeSalvo to Mary Sullivan’s murder until today,†said Daniel F. Conley, the Suffolk County district attorney, at a news conference on Thursday.

“We feel really horrible for the families of the victims and our deepest regards go out to the Sherman family,†said Mr. Jewell, referring to the family of Ms. Sullivan. “No one deserves to die the way Mary Sullivan did, and we hope that the news conference brings some closure to the families of the victims.â€

He said the announcement also brings much needed closure to his family. “As one of four investigators handpicked for the Strangler Bureau, a special task force solely dedicated to catching the Boston Strangler, Phil was also the last man standing in seeking a conviction,†he said.

At the time, he said, prosecutors believed they did not have sufficient physical evidence to move ahead with a case.

In the documentary, Mr. Jewell and his uncle describe how an anonymous tip to the head of security at Massachusetts General Hospital led the team to focus on Mr. DeSalvo.

“That was the day Albert DeSalvo came into my father’s life,†said the detective’s son, John DiNatale. “From then on, he consumed my father’s life until the day he died in January 1987.â€

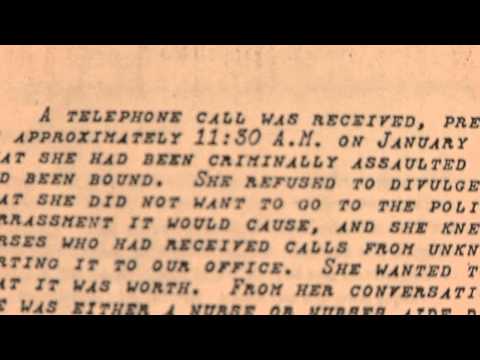

In a short video clip, Mr. DiNatale read from his father’s journal about what the head of security at the hospital told him. It was on Jan. 28, 1965, that a hospital employee, who refused to divulge her name, told hospital security officials she had been criminally assaulted and bound in her apartment. She told them to tell police to look at Mr. DeSalvo but she did not say why. She also said that she did not report the crime to police, because she was too embarrassed.

In this clip, John DiNatale describes how his father tried to gather as much information as possible on Albert DeSalvo, going through everything from criminal records to parking tickets.

Mr. DeSalvo was ruled out as a possible suspect for several of the murders because it appeared that he was in jail at the time of the killings, but Mr. DiNatale said his father uncovered a clerical error in the correction facility’s records that showed Mr. DeSalvo was actually out of prison at the time the murders occurred.

Mr. DeSalvo was arrested on breaking and entering charges in Cambridge, Mass., in 1965. He later confessed to the crimes, but was not prosecuted for the murders.

“My grandfather wanted to see the conviction through,†Mr. Jewell said. “But everyone was O.K. with the strangler just being off the streets. They didn’t see the need.†He said his grandfather, who later went on to serve as a technical adviser for a 1968 movie about the case, left the Boston Police Department and opened up his own private investigation firm.

But he remained troubled by the questions that some people had about Mr. DeSalvo’s guilt.

Among those raising questions over the years about the confession and how law enforcement managed the case was the family of Ms. Sullivan, who had moved to Boston from her family’s home on Cape Cod only a few days before her murder.

Casey Sherman, Ms. Sullivan’s nephew, said the new evidence presented on Thursday “provides an incredible amount of closure.†He talked about his own doubts about Mr. DeSalvo and the impact of his young aunt’s death on his mother, at the news conference.

Mr. DeSalvo was stabbed to death at Massachusetts Correctional Institution-Walpole in 1973. He was serving a life sentence for rape and other crimes.

Even if there is a clear DNA match, however, my colleague Ms. Bidgood reports that doubts still remain about whether Mr. DeSalvo was in fact the Boston Strangler or just one of several people who committed the murders because of inconsistencies in his confession.