|

DXPG

|

Total Pageviews |

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Today’s Scuttlebot: The Mesmerized Stare, and Google’s Weird Questions

Xbox Reversal Won’t Stop the Inevitable

It seemed like a spectacular flip-flop: Microsoft on Wednesday reversed a couple of controversial policies about how its new Xbox One game console will operate, both of which would probably have slammed the brakes on the used games business.

Gamers shrieked with the fury of a thousand dying aliens out of “Halo†over the Microsoft policies. Players love being able to finish a game, trade it in for credit at a GameStop or another retail store and buy another one to keep feeding their game habits. Game publishers, on the other hand, get hives over used games because they haven’t been able to make any money from the resale of secondhand titles.

Microsoft’s reversal on Wednesday may quiet some of the criticism it has received in recent weeks. It will no longer require that the Xbox One be plugged into an Internet connection, which, among other things,would have prevented players from making cpies of games and giving or selling game discs to others.

Microsoft previously said that it would allow games publishers to opt out of allowing the resale of Xbox One games and to let them charge fees associated with that process. Now it says it won’t impose any restrictions on the resale of games.

The company’s reversal has only postponed changes that will most likely result in used games fading away, though.

That’s because it’s a question of when, not if, the physical discs on which most console games are now delivered go away. Mobile and PC games have already ushered in the era of downloadable games. People who buy games online can’t typically resell them because of the licensing restrictions that apply to digital media, just as they can’t resell movies they buy on iTunes.

In an important and overlooked development, Microsoft recently showed just how seriously it intended to nudge its customers toward the digita! l downloading of games. The company said digital versions of Xbox One games would be available on the same day that disc-based versions of those same games went on sale.

“I think this discussion about the used games business two or three years from now will be largely irrelevant,†said Evan Wilson, an analyst at Pacific Crest Securities who follows the games business.

In the meantime, Microsoft’s change bought some breathing room for GameStop, one of the few mass retailers dedicated to selling games and a company that is seeking to adapt to the digital future through various initiatives. In its most recent quarter, 30.7 percent of its sales and nearly half of its gross profits came from used game products.

On Thursday, the day after Microsoft announced its reversal, GameStop’s shares rose 6.25 percent to $40.94.

Facebook Is Betting Longer Videos Are Better

What’s the perfect length for video shot and shared via a mobile phone â€" 15 seconds or six?

Facebook is betting that longer is better.

The social networking giant introduced a video feature as part of its Instagram photo app on Thursday. The feature, which makes it easy to record and post video with a few touches of the screen, strongly resembles the Vine service introduced by Twitter about five months ago.

Shooting short videos is a popular activity among mobile users, with Vine growing to nearly 20 million users since its introduction. Instagram, which already has 130 million users, will probably supercharge growth of the category through its sheer size.

Size, or rather length, will be a crucial battleground between the services.

Vine allows users to record only six seconds of video. Instagram allows users to post up to 15 seconds of video, and they can choose to dlete and rerecord segments to make a more cinematic experience â€" or what one of Instagram’s founders, Kevin Systrom, called a “better collage.â€

Mr. Systrom, who introduced the video feature at a news conference at Facebook’s Menlo Park, Calif., headquarters, said his team believed that 15 seconds was the “Goldilocks†length â€" not too long and not too short.

Instagram is also offering its users a palette of 13 filters to modify the videos, much as it does for still photos.

A demonstration of the new Cinema feature.

Perhaps the biggest difference from Vine is Instagram’s image stabilization feature, called Cinema. Hand-held cameras like smartphones often produce jumpy videos, and Instagram’s technology smooths that out. Mr. Systrom said it made amateur video look more professional.

“We’ve worked a ton on making it fast, simple and beautiful,†Mr. Systrom said.

When users browse a page with Instagram video, it wil! l play automatically once, then stop. (Vine video loops endlessly, to the annoyance â€" or delight â€" of many users.)

Although Instagram video is immediately available to both Apple iOS and Android users, the image stabilization feature is now only on the iOS version.

For now, neither Instagram nor Vine has ads. But as my colleague Jenna Wortham and I write in this accompanying article, that may well change as both Facebook and Twitter seek new sources of revenue. Online video advertising is growing quickly, with spending in the United States expected to top $4 billion this year, according to estimates from the research firm eMarketer.

Facebook Is Betting Longer Videos Are Better

What’s the perfect length for video shot and shared via a mobile phone â€" 15 seconds or six?

Facebook is betting that longer is better.

The social networking giant introduced a video feature as part of its Instagram photo app on Thursday. The feature, which makes it easy to record and post video with a few touches of the screen, strongly resembles the Vine service introduced by Twitter about five months ago.

Shooting short videos is a popular activity among mobile users, with Vine growing to nearly 20 million users since its introduction. Instagram, which already has 130 million users, will probably supercharge growth of the category through its sheer size.

Size, or rather length, will be a crucial battleground between the services.

Vine allows users to record only six seconds of video. Instagram allows users to post up to 15 seconds of video, and they can choose to dlete and rerecord segments to make a more cinematic experience â€" or what one of Instagram’s founders, Kevin Systrom, called a “better collage.â€

Mr. Systrom, who introduced the video feature at a news conference at Facebook’s Menlo Park, Calif., headquarters, said his team believed that 15 seconds was the “Goldilocks†length â€" not too long and not too short.

Instagram is also offering its users a palette of 13 filters to modify the videos, much as it does for still photos.

A demonstration of the new Cinema feature.

Perhaps the biggest difference from Vine is Instagram’s image stabilization feature, called Cinema. Hand-held cameras like smartphones often produce jumpy videos, and Instagram’s technology smooths that out. Mr. Systrom said it made amateur video look more professional.

“We’ve worked a ton on making it fast, simple and beautiful,†Mr. Systrom said.

When users browse a page with Instagram video, it wil! l play automatically once, then stop. (Vine video loops endlessly, to the annoyance â€" or delight â€" of many users.)

Although Instagram video is immediately available to both Apple iOS and Android users, the image stabilization feature is now only on the iOS version.

For now, neither Instagram nor Vine has ads. But as my colleague Jenna Wortham and I write in this accompanying article, that may well change as both Facebook and Twitter seek new sources of revenue. Online video advertising is growing quickly, with spending in the United States expected to top $4 billion this year, according to estimates from the research firm eMarketer.

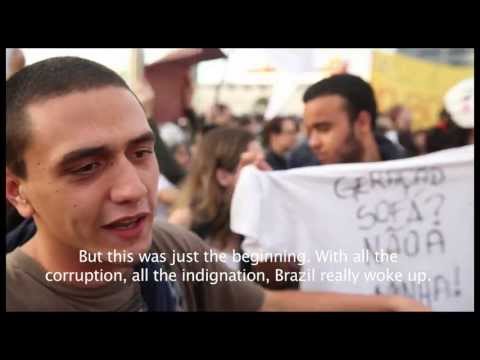

Brazil’s Protesters, in Their Own Words

As my colleague Simon Romero reports, Brazil is braced for another round of protests on Thursday, with demonstrations planned for dozens of cities, even after the authorities retreated from plans to raise bus fares across the country in the face of massive street protests.

The size and intensity of the demonstrations has created an instant demand in the global media for English-speaking academics and journalists who can explain the root causes of the protests tothe rest of the world. Less often heard are the voices of the protesters themselves, and Brazilians who sympathize with their demands.

That makes the work of two contributors to the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo’s blog “From Brazil,†particularly valuable. Reporting from the streets of São Paulo this week, the filmmaker Otavio Cury and Dom Phillips, a British journalist based in Brazil, have produced two excellent video reports, with English subtitles, in which Brazilians explain in clear terms the frustration and anger behind the movement.

In one video recorded on Monday night, a 46-year-old maid named Maria Lucia who was trying to make her way home through that night’s demonstration in São Paulo stopped to explain why sh! e supported the protests. The second video report amplifies the voices of eight protesters who marched that night in a crowd estimated at more than 65,000.

Mr. Cury offered one more, wordless, glimpse of the energy on São Paulo’s streets in a brief video clip of a protest marching band recorded during a demonstration Tuesday night.

Daily Report: The Deepening Ties Between the N.S.A. and Silicon Valley

Increasingly deep connections between Silicon Valley and the National Security Agency reflect the degree to which they are now in the same business. Both hunt for ways to collect, analyze and exploit large pools of data about millions of Americans. The only difference is that the N.S.A. does it for intelligence, and Silicon Valley does it to make money, James Risen and Nick Wingfield report in The New York Times.

Silicon Valley has what the National Security Agency wants: vast amounts of private data and the most sophisticated software available to analyze it. The agency in turn is one of Silicon Valley’s largest customers for hat is known as data analytics, one of the valley’s fastest-growing markets. To get their hands on the latest software technology to manipulate and take advantage of large volumes of data, United States intelligence agencies invest in Silicon Valley start-ups, award classified contracts and recruit technology experts like Max Kelly, a former chief security officer for Facebook.

“We are all in these Big Data business models,†said Ray Wang, a technology analyst and chief executive of Constellation Research, based in San Francisco. “There are a lot of connections now because the data scientists and the folks who are building these systems have a lot of common interests.â€

One example: When Mr. Kelly left Facebook in 2010, he did not go to Google, Twitter or a similar Silicon Valley concern. Instead, the man who was responsible for protecting the personal information of Facebook’s more than one billion users from outside attacks went to work for another giant institution that manages and analyzes large pools of data: the National Security Agency.

The disclosure of the spy agency’s program called Prism, which is said to collect the e-mails and other Web activity of foreigners using major Internet companies like Google, Yahoo and Facebook, has prompted the companies to deny that the agency has direct access to their computers, een as they acknowledge complying with secret N.S.A. court orders for specific data.

Yet technology experts and former intelligence officials say the convergence between Silicon Valley and the N.S.A. and the rise of data mining â€" both as an industry and as a crucial intelligence tool â€" have created a more complex reality.

“These worlds overlap,†said Philipp S. Krüger, chief executive of Explorist, an Internet start-up in New York.

Daily Report: The Deepening Ties Between the N.S.A. and Silicon Valley

Increasingly deep connections between Silicon Valley and the National Security Agency reflect the degree to which they are now in the same business. Both hunt for ways to collect, analyze and exploit large pools of data about millions of Americans. The only difference is that the N.S.A. does it for intelligence, and Silicon Valley does it to make money, James Risen and Nick Wingfield report in The New York Times.

Silicon Valley has what the National Security Agency wants: vast amounts of private data and the most sophisticated software available to analyze it. The agency in turn is one of Silicon Valley’s largest customers for hat is known as data analytics, one of the valley’s fastest-growing markets. To get their hands on the latest software technology to manipulate and take advantage of large volumes of data, United States intelligence agencies invest in Silicon Valley start-ups, award classified contracts and recruit technology experts like Max Kelly, a former chief security officer for Facebook.

“We are all in these Big Data business models,†said Ray Wang, a technology analyst and chief executive of Constellation Research, based in San Francisco. “There are a lot of connections now because the data scientists and the folks who are building these systems have a lot of common interests.â€

One example: When Mr. Kelly left Facebook in 2010, he did not go to Google, Twitter or a similar Silicon Valley concern. Instead, the man who was responsible for protecting the personal information of Facebook’s more than one billion users from outside attacks went to work for another giant institution that manages and analyzes large pools of data: the National Security Agency.

The disclosure of the spy agency’s program called Prism, which is said to collect the e-mails and other Web activity of foreigners using major Internet companies like Google, Yahoo and Facebook, has prompted the companies to deny that the agency has direct access to their computers, een as they acknowledge complying with secret N.S.A. court orders for specific data.

Yet technology experts and former intelligence officials say the convergence between Silicon Valley and the N.S.A. and the rise of data mining â€" both as an industry and as a crucial intelligence tool â€" have created a more complex reality.

“These worlds overlap,†said Philipp S. Krüger, chief executive of Explorist, an Internet start-up in New York.